At the Edge

organized in collaboration with Dennis Scholl, presented at Oolite Arts

June 8 – Sept. 11, 2022

At the Edge is an exhibition of female artists using abstraction as a means to investigate and challenge the boundaries of material, process, and environment. Their approaches to abstraction are built from interdisciplinary practices that span both two and three dimensional space. While removing formal ties to nature, the works–centered around line, form and color–offer up room for a deep well of meaning and readings to emerge. The gallery becomes the site that assembles this multiplicity that abstraction provides. Drawing from notions of labor, resistance, and transformation, the works in the exhibition survey abstraction as a space that lies at the edge.

Photos by Pedro Wazzan.

When we stand at the edge, we stand amid a multitude of opportunities, positioned between where we came from and where we might go next. This is a fertile location and point of view. Similarly, the space between representation and abstraction is a rich mine for meaning, removing preconceived notions and ideas, and loosening the mind to explore and expand.

For Georgia Lambrou, the explorations in abstraction stem from an interest in the built world, the spaces and structures that we navigate and exist within in our daily lives that shape our relationships. As Gaston Bachelard wrote in The Poetics of Space, “A house that has been experienced is not an inert box. Inhabited space transcends geometrical space.”1

Also directly responding to physical space, Nathalie Alfonso explores abstraction as a method of repetition and endurance, this process playing a crucial role in the creation of her works. Built from the relationship she develops with each space in which she works, the investment of time and her bodily presence is demarcated through her use of materials — primarily charcoal and graphite — which record the labor of the hand and oils from her fingertips.

In Devora Perez’s practice, abstraction allows a blurring of dimensions to occur as her work operates in the spaces between painting, sculpture, and installation. Although minimal, and subtle in form, her three-dimensional floor works disrupt ideas of structure, utility, and definition. She creates works that serve as a form of resistance, pushing beyond any singular limitation, with interactions between space, material, and light adding layers of meaning.

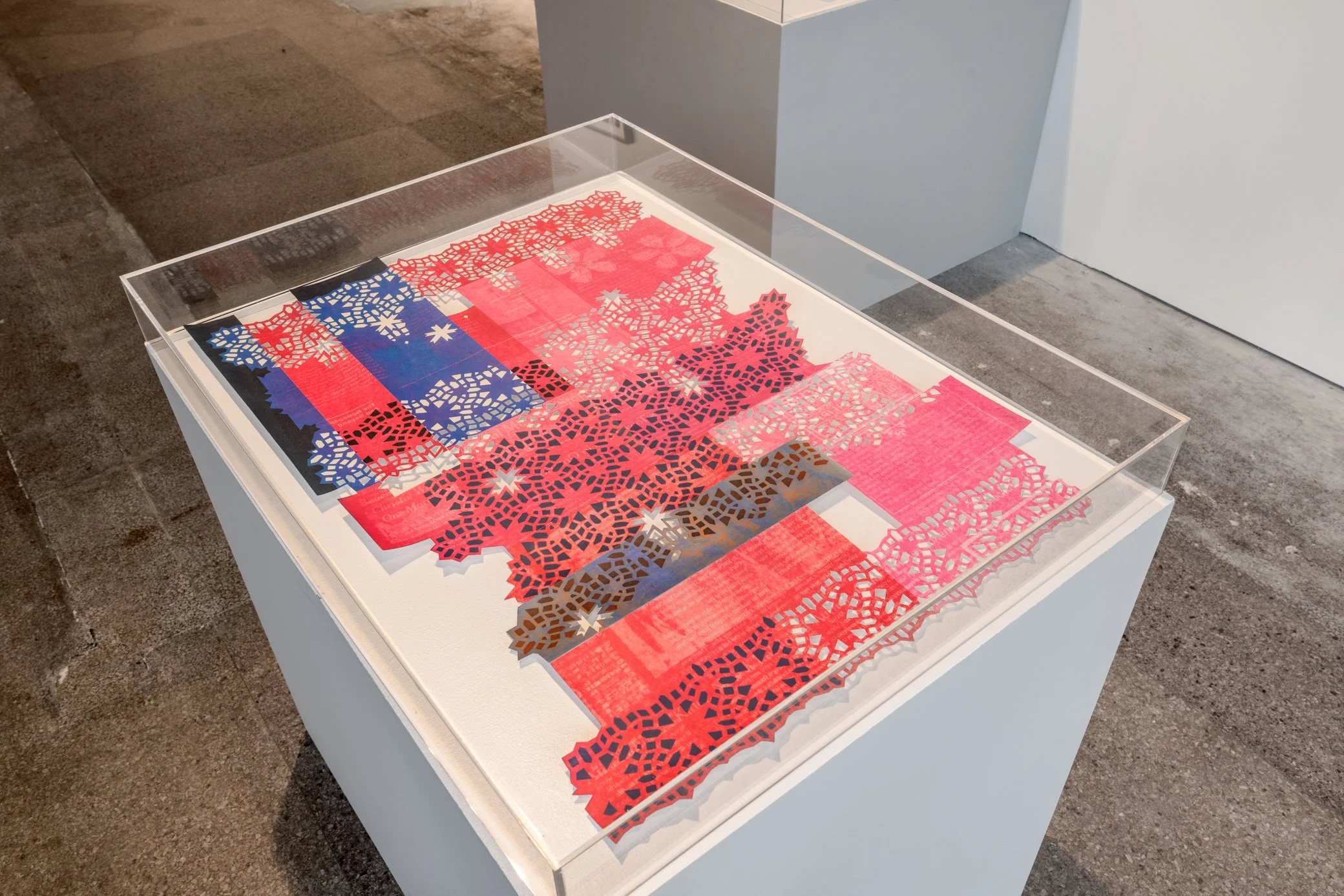

Language and communication are starting points for Donna Ruff. Using newspapers as both linguistic content and source of material, she cuts away sections and abstracts original messages, the geometric motifs of the handcut pieces signifying, in her own words, “a sense of loss and time passing in abstract terms — as fragmentations of shape and pattern.”

Jennifer Printz uses abstraction as a parallel to poetry, her works often gesturing at a loose narrative that allows for many meanings to take shape. A sense of instinct and freedom guides the decision-making process of her work, which often becomes a meditative place of making. Ambiguous forms found in nature are referenced, denoting places where the natural world exists as undefined and abstract.

Lastly, the work of Karen Rifas is both monumental and delicate. The formal qualities of her work — bold colors, shapes, and lines — truly embody what abstraction is and may still become, with endless possibilities and abundant ground for developing meaning. Rifas’s exploration of color over the last decade is informed by her experience as a dancer and ties to Miami, with its tropical palette.

Working at the edges, with all of the challenges and possibilities that embodies, each of the exhibiting artists eschews the gestural form, choosing instead to embrace abrupt transitions between materials, mark-making, and fields of color. Together, their works interrogate assumptions about geometric abstraction, its conventional methods and formal beauty, and instead pose salient new questions about the edges we all find ourselves poised upon today.

1 Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, 1957 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), 47.